The Best Blacktresses: 1950s — Dandridge was the first Black woman nominated for Best Actress at the Oscars, for her groundbreaking role in “Carmen Jones.” Just 10 years later, she died penniless and all but forgotten.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Best-Blacktresses-Dorothy-Dandridge-9912d9c46afa4b69b8a2c63f174eb379.jpg) Photo:

Photo:

©20thCentFox/Courtesy Everett Collection; Design: Alex Sandoval

The Best Blacktresses is a weekly, seven-part series dedicated to the 13 Black women and their 14 performances (shout-out to two-time nominee Viola Davis) nominated for Best Actress in a Leading Role the Academy Awards’ nearly 100-year history.

“My plan is that while in Hollywood I will be approached by an imminent producer, at the Ivy no doubt, to star in the lush film version of the life of Ms. Dorothy Dandridge. Yes, that noble Blacktress, who never played domestic help. And then who’s career was crushed by the white Hollywood machine.” — Noxeema Jackson, To Wong Foo, Thanks for Everything! Julie Newmar

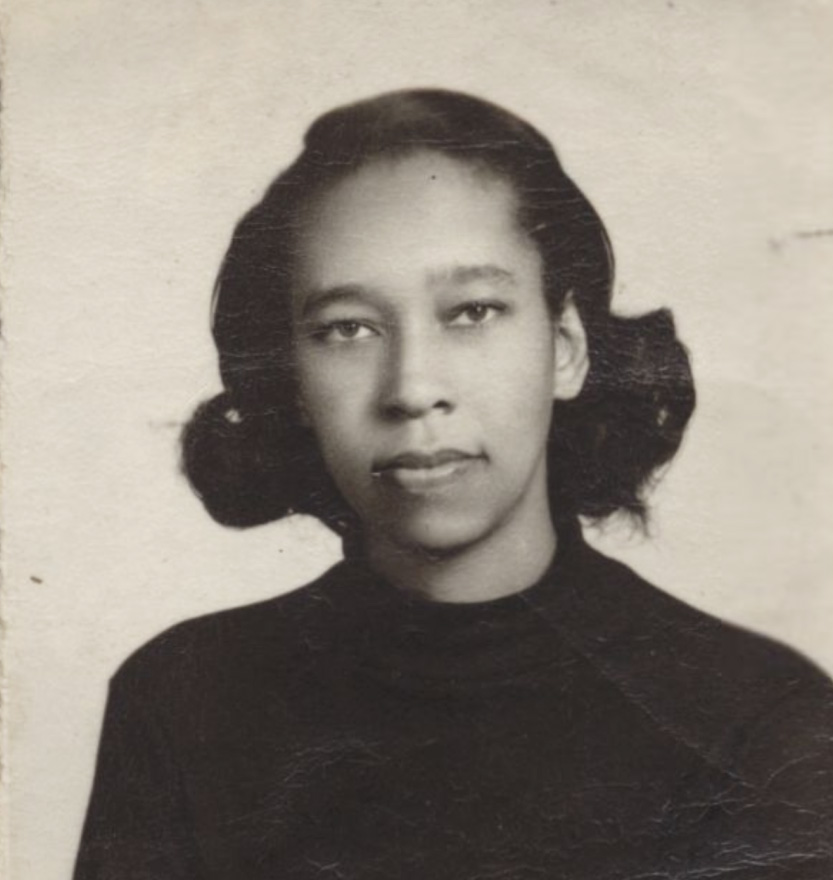

What Dorothy Dandridge accomplished was extraordinary.

Her role in 1954’s Carmen Jones was unlike anything given to a Black actress at the time: a 𝓈ℯ𝓍y, 𝓈ℯ𝓍ual, headstrong, independent woman who was neither a maid nor subservient to anyone.

Dandridge could’ve and should’ve represented a bold, new direction for Hollywood — she had the right combination of talent, beauty, ambition, and chutzpah that makes for the greatest stars — but instead she was a tragic footnote whose promise would go unfulfilled for another five decades.

“Carmen Jones was the best break I’ve ever had,” Dandridge once said. “But no producer ever knocked on my door. There just aren’t that many parts for a Black actress.”

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/The-Best-Blacktresses--Dorothy-Dandridge-1954010120-2cca6225abb7418c8f7c7a1040ec8897.jpg) Dorothy Dandridge and Harry Belafonte in ‘Carmen Jones’.

Dorothy Dandridge and Harry Belafonte in ‘Carmen Jones’.

getty

The film came out five months after Brown v. the Board of Education, determining that separate was not equal and ruling segregation unconstitutional. In the midst of this social upheaval in the United States, Dandridge was poised to cross over in a way that no other Black performer had done. Directed by Otto Preminger, Carmen Jones turned Dandridge into a sensation, the first Black leading lady.

In 1955, Dandridge was nominated for the Best Actress Oscar for her breakthrough role, becoming the first Black performer to be nominated in a lead acting category. In 1940, Hattie McDaniel became the first Black performer to win an Oscar, for Best Supporting Actress for Gone With the Wind. McDaniel’s win was a watershed moment, but it was also indicative of the roles offered and available to Black people — the simple, stereotypical servants of white people.

In 1935, tap dancer Jeni Le Gon became the first Black woman to sign a long-term contract with a major film studio when she inked a deal with MGM. However, MGM didn’t know what to do with Le Gon (she wasn’t even allowed to sit in the studio’s main dining room), so her contract was terminated shortly after she signed it.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/The-Best-Blacktresses--Dorothy-Dandridge-1935053022-eb9e04b577394697bb26d7bfc8c33e08.jpg) Jeni Le Gon.

Jeni Le Gon.

getty

Then in 1942, Lena Horne signed a seven-year contract with MGM, and this time, she got to star in two all-Black productions, Cabin in the Sky and Stormy Weather. The rest of Horne’s run at MGM was less auspicious. In films that starred white actors, the former nightclub singer was relegated to musical numbers that bore no weight on the main plot so that she could be easily removed from cuts in the South, where distributors refused to show Black performers.

Horne appeared in one such film, the 1946 MGM extravaganza Till the Clouds Roll By, a highly fictionalized biopic of composer Jerome Kern, singing “Can’t Help Lovin’ Dat Man” from Show Boat. Horne thought the segment was basically a screen test for the studio’s upcoming production of the Kern musical. She seemed a natural choice for Julie, a mixed race singer passing for white while married to a white man. The part ultimately went to Horne’s good friend, the very white Ava Gardner. Disillusioned, Horne left Hollywood shortly after that, and went on to a long career as a nightclub entertainer.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/The-Best-Blacktresses--Dorothy-Dandridge-1946010123-417fe49b873e49e1b17a755719710863.jpg) Lena Horne.

Lena Horne.

Michael Ochs Archive/Getty

Around that time, Dandridge was making waves on the nightclub circuit as a singer and dancer with the occasional uncredited film part. She had caused a minor stir in 1951’s Tarzan’s Peril as the scantily clad African queen Melmendi, landing on the cover of Ebony with the headline, “Hollywood’s newest glamour queen.”

In 1953, Dandridge had her first starring role in the drama Bright Road, playing a demure school teacher. Director Otto Preminger had that image of Dandridge in his head when she auditioned for the lead role in Carmen Jones, an all-Black adaptation of Bizet’s opera Carmen that had been a hit on Broadway.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/The-Best-Blacktresses--Dorothy-Dandridge-1945010124-7287596f7ba44e27a8cdc8bcca86437d.jpg) Dorothy Dandridge c. 1945.

Dorothy Dandridge c. 1945.

Hulton Archive/Getty

Preminger suggested the rather prim Dandridge audition for the role of the rather prim Cindy Lou, instead. Determined to land the title role, the then-31-year-old pleaded with Preminger to let her return the next day and this time she dressed the part of a wanton wild woman, shocking Preminger into giving her a screen test. After the director was sufficiently blown away, he cast Dandridge as Carmen Jones.

Once the excitement of getting the role wore off, reality set in for Dandridge and she began to doubt if she could do justice to this paradigm-shifting part. After all, this wasn’t just a big break for her, it was a big break for the entire African American race, a weight she and other Black artists breathing rarified air at the time no doubt shared. Dandridge tried to pull out of the film, prompting Preminger to drive to her house to reassure the star — and as these things tend to lead to another, the pair started a years-long affair.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/The-Best-Blacktresses--Dorothy-Dandridge-2024013026-d6ffb550d8f446eba255b3722d885f2b.jpg) Dorothy Dandridge on the cover of ‘Ebony’.

Dorothy Dandridge on the cover of ‘Ebony’.

As the titular femme fatale in Carmen Jones, Dandridge eats the screen alive. She’s seductive and ferocious, in love only with her own freedom. She’s not only unlike any Black character in film to that point, Carmen Jones was unlike most women in film. And so of course she has to pay for it. This being an opera, and this being the 1950s, Carmen [70-year-old spoiler alert!] dies at the end at the hands of a young, inexperienced Harry Belafonte.

While the film itself has its issues — Belafonte, a national treasure, had not grown into a good film actor by this point and the musical sequences vary from exhilarating to tiresome — Dandridge remains the movie’s greatest legacy (and let’s not forget Ms. Pearl Bailey, whose 𝐛𝐢𝐫𝐭𝐡day should be a national holiday). And though both she and Belafonte had been known as singers, their voices were dubbed (as was common practice back then) to achieve the operatics of Bizet’s score. But that doesn’t take away from Dandridge’s performance.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/The-Best-Blacktresses--Dorothy-Dandridge-2024013027-697884595678407fb61b9942ccb91d77.jpg) Dorothy Dandridge in ‘Tarzan’s Peril’.

Dorothy Dandridge in ‘Tarzan’s Peril’.

everett

Carmen Jones should’ve been the beginning of an illustrious career for Dandridge. In 1955, she signed a three-picture deal with 20th Century Fox and that same year, she appeared at the Oscars as a nominee and a presenter, where she was obviously overwhelmed with the emotion of the night.

“If I seem a little nervous,” she said before presenting the Best Editing award, “this is as big a moment for me as it will be for the winner of this award.”

Dandridge was the first Black presenter at the Academy Awards — when McDaniel won, the actress had to sit at a segregated table away from the rest of the white attendees, including her Gone With the Wind costars. Dandridge was also the first Black woman featured on the cover of Life magazine. She was a new kind of Black actress: a leading lady. And, also importantly, a 𝓈ℯ𝓍 symbol.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/The-Best-Blacktresses--Dorothy-Dandridge-2024013025-1e370700e5454cd5a16bce911e0969a3.jpg) Dorothy Dandridge on the cover of ‘Life’.

Dorothy Dandridge on the cover of ‘Life’.

Her image was markedly different than that of McDaniel’s matronly mammies or Horne’s chaste songstresses pining away on a pillar, so easily erased to satisfy white Southern sensibilities. Here was a Black woman with depth and dimension, a woman who deserved, and whose talent demanded, her own stories, not simply to be relegated to playing second-fiddle in someone else’s. Sure, Dandridge may have been a new kind of star, but Hollywood was and remains an old kind of town, so much so that Black actresses still have to struggle to take center stage in their own stories.

The 1955 Best Actress Oscar race is one of the greats: Dandridge was up against frontrunner Judy Garland for her epic turn in A Star Is Born, the previous year’s winner Audrey Hepburn in Sabrina, Jane Wyman in Magnificent Obsession, and eventual winner Grace Kelly in The Country Girl. Though Kelly won, the night is best remembered as the one Dandridge made history.

But just as MGM had not known what to do with Le Gon or Horne, Fox struggled to figure out how best to use Dandridge, who refused (like Horne before her) to play roles as slaves or domestics. After the unparalleled success of Carmen Jones, Dandridge languished on the vine at Fox for three years until 1957’s Island in the Sun.

Dandridge also struggled with being “suddenly projected into a Caucasian orbit,” as she wrote in her autobiography, Everything and Nothing, knowing that she would be “carrying the Negro race,” that is, she had to be representative of all Black people, a burden that should be placed on no one. But as the first and only, she was a pioneer on untested ground — ground that could easily be ripped out from under her.

“While experiencing what seemed to be a full acceptance, I encountered not-yetness,” Dandridge wrote. “Whites weren’t quite ready for full acceptance even of me, purportedly beautiful, passable, acceptable, talented, called by the critics every superlative in the lexicon employed for a talented and beautiful woman.”

Dandridge made a handful of more films, chief among them 1959’s controversial Porgy and Bess, for which both she and costar Sidney Poitier were nominated for lead acting Golden Globes, but her movie career more or less ended with the ‘50s. All that promise, all that talent, all for naught.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/The-Best-Blacktresses--Dorothy-Dandridge-2024013021-2e5ebbc7281f432fa7fbbadfb6df4b61.jpg) Dorothy Dandridge at the 1955 Academy Awards.

Dorothy Dandridge at the 1955 Academy Awards.

Dandridge died in 1965, penniless and all but forgotten. While she had her share of personal problems and tragedies, her brief, bright film career would become a beacon, and a warning, for other Black actresses. She showed what was possible…and also the limitations of those possibilities when the world has yet to accept you as fully human.

Her two deaths — her death as a movie star and her death as a human being — seemed to hang like a pall over the entire decade. Not a single Black performer was nominated for Best Actress at the Oscars in the 1960s. During that decade, Black women were rarely, if ever, the stars of films, let alone given the rich, complex roles that made for Oscar bait.

In contrast, in 1964, Poitier became the first Black Best Actor Oscar winner when he took home the trophy for Lilies of the Field. It would be 47 years after Dandridge’s historic nomination for a Black woman to actually win a Best Actress Oscar. Halley Berry, who earned an Emmy and Golden Globe for the 1999 TV movie Introducing Dorothy Dandridge, won in 2002 for Monster’s Ball. More than 20 years later, Berry is the first and only Black Best Actress winner. But more on that later.