As the Angels outfielder and WAR machine turns 28, he looks poised to lead his league in home runs for the first time. What other statistical belts could he claim before his career is over?

On Tuesday, Mike Trout’s last day as a 27-year-old, the Angels center fielder went 1-for-3 with a walk and a 412-foot home run. It wasn’t surprising to see Trout filling every line next to his name in the box score, because almost everything he accomplished on Monday bolstered his stats in a category in which he’s previously led the league.

Scoring two runs? Trout has led his league in runs scored four times. Driving in a run? He led his league in that once and is currently leading it again. Amassing five total bases? Trout led the league in total bases in 2014. Drawing a walk? He already owns three AL walk titles, and as of today he’s in line for a fourth. He also struck out twice on Tuesday, and he once led the league in that too. The only outcome he managed on Tuesday that he hasn’t led his league in is homers, but his 38 this season give him six more than his closest AL competitor.

Trout’s contribution on Tuesday was worth 0.1 WAR at FanGraphs, where he leads the majors by more than a win, with 7.6 on the season. He also leads the majors in Baseball-Reference WAR and Baseball Prospectus WARP, and he surpasses several Hall of Famers in career WAR(P) every month. For once, though, let’s not fixate on Trout leading the world in WAR. Let’s talk about Trout leading the league in almost everything else.

WAR, which was added to FanGraphs in 2008 and to Baseball-Reference in 2010, arrived at just the right time to help us appreciate Trout, who made the majors in July 2011. The relationship that Trout has forged with WAR is symbiotic. The holistic stat allows us to quantify the full extent of his greatness, because it accounts for his playing time, adjusts for his offensively unfavorable ballpark, and places his value as an above-average base runner and center fielder on the same scale as his hitting, reconciling concepts that once were harder to hold in one’s head. (Not only has Trout been by far baseball’s best hitter since he came up, he’s been close to its most valuable base runner.) Trout, in turn, has given us a window into why WAR matters, first via his MVP battles with Miguel Cabrera—a player whose peak offered flashier traditional stats but less overall value—and more recently through his ascent into the inner circle of the game’s greats.

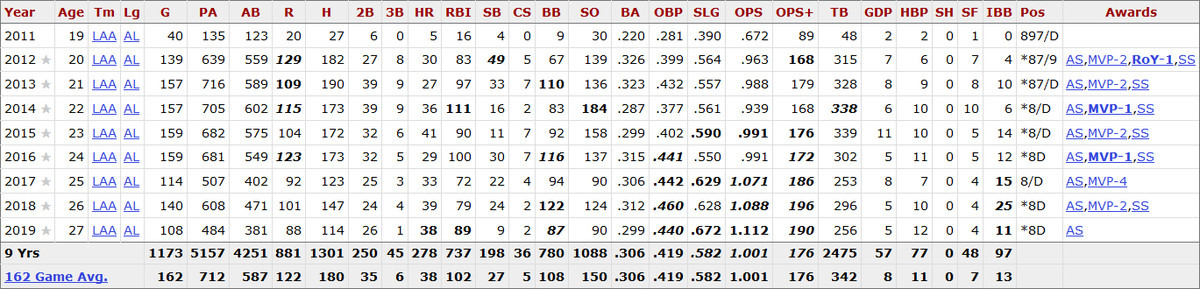

Trout, who turns 28 on Wednesday and is slashing .299/.440/.672 on the season, has become synonymous with WAR in much the same way that Ty Cobb was with batting average, Rickey Henderson was with stolen bases, and Mariano Rivera was with saves. Without WAR, we would know Trout is great, but would we understand that he’s off to the best start of all time? At the very least, the case would be harder to make if we couldn’t conveniently link to leaderboards that summed it up with one number.

Although that number is handy to have, it takes many more to capture the complexity of Trout’s standout s𝓀𝒾𝓁𝓁s. One could infer from his high WAR values that Trout is an exceedingly well-rounded player, as able at the plate as he is capable beyond it. But the best way to internalize Trout’s balance at bat with one glance is to visit his Baseball-Reference player page and eyeball the bold and italicized figures, which represent league-leading and major-league-leading performances, respectively. Not only is Trout’s page rich in both, but it’s bold across the board, boasting elite totals that span the spectrum from speed to patience to power.

In October 2016, Effectively Wild podcast cohost Sam Miller and I drafted statistical categories in which Trout hadn’t yet led his league. “One of the great things about his player page that’s really almost unlike any other player page is that every year he gets new bold ink,” Sam said at the time, noting that each season, Trout turns into “a totally different best player in baseball.” True to form, Trout has since crossed off one of those unclaimed categories—intentional walks, which he’s now led the league in twice and looks likely to lead in again—and is poised to x out another, home runs.

Eight years into his big league career, Trout’s capacity to be the best in his league—not just by repeatedly leading in a small selection of statistical categories, but by broadening the range of categories where his seasonal stats have been bold at least once—is entering historic territory. To put Trout’s league leadership into perspective, I asked Dan Hirsch of Baseball-Reference to send me a list of every hitter in history, along with the number of times each of them led his league in 17 specified stats, all of them available in the basic B-Ref stat line. Then I calculated which hitters have led in the widest assortment of those stats.

The 17 stats are as follows: games, plate appearances, runs, hits, doubles, triples, home runs, runs batted in, stolen bases, walks, batting average, on-base percentage, slugging percentage, on-base plus slugging, total bases, hit by pitches, and intentional walks. I omitted categories players try not to lead in (such as strikeouts and times caught stealing or grounding into double plays), as well as those with dubious value and/or inconsistent definitions (sacrifice bunts and sacrifice flies) and some that seemed redundant given the stats selected above (at-bats, OPS+).

If Trout maintains his home run lead and crosses that category off his bold-ink bingo card this year, he’ll have led his league in 10 of the 17 stats, leaving him stymied in seven: games, plate appearances, hits, doubles, triples, batting average, and hit by pitches. Just by getting to 10, he’ll have joined a group of only 37 players with double-digit tallies of categories collected, and five of those (Ross Barnes, Tip O’Neill, Benny Kauff, Hugh Duffy, and Harry Stovey) got there by playing in lesser leagues. Only 22 players (including Barnes, O’Neill, and Stovey) have topped 10.

Not a lot of players have led their leagues in a more varied assemblage of stats than Trout. Consider this, though: It’s gotten much more difficult to be a league leader. Not just because baseball’s caliber of play keeps improving, making it more difficult for one player to be the best in many areas, but because the sport has expanded, creating more competition. Of the 37 non-Trout players who’ve led in at least 10 categories, all but seven debuted when each league featured only eight teams. All but three—Alex Rodriguez, Albert Pujols, and Miguel Cabrera—debuted before the two most recent rounds of expansion. And all but the latter two arrived before MLB expanded to 30 teams. Trout made his debut in a 14-team league and has played all but his first full season in a 15-team league. Getting to 10 in Trout’s time is much more impressive than it was during the days of Dan Brouthers, Tris Speaker, or Duke Snider.

On top of that, Trout is just turning 28. Excluding the entrants from lesser leagues, only 13 previous players got to 10 categories by the end of their age-27 seasons, and only seven—Stan Musial, Rogers Hornsby, Ted Williams, Cobb, Carl Yastrzemski, Mickey Mantle, and Joe Medwick—surpassed 10 by that age. Most players on the list added to their totals after Trout’s age, and some greats picked off categories when their 20s were distant memories. Musial’s last new category came at 34, when he led the NL in hit by pitches for the first and only time; Hank Aaron added intentional walks at age 37, and Willie Mays landed walks at age 40.

Even if a home run crown proves to be Trout’s final frontier, he’ll have collected some unlikely combinations that set him apart from most members of the 10-categories club. One wouldn’t expect many hitters to have led their leagues in both intentional walks and stolen bases, two feats on Trout’s résumé. For one thing, the type of hitter who’s capable of leading the league in steals isn’t typically also the type to inspire so much fear at the plate that pitchers would put him on. For another, pitchers have extra incentive not to issue free passes to players who can make them pay on the basepaths. Consequently, only two other hitters in history have matched this Trout achievement: Ichiro Suzuki and Pee Wee Reese—and Reese racked up 22 of his NL-leading 29 intentional walks in 1947 when he was batting eighth, ahead of the pitcher.

If he doesn’t surrender his home run lead, Trout will soon become only the seventh player to have led his league in both homers and stolen bases—and the first since Mays, who joined the exclusive club in 1956. Four of the previous five members played during the deadball era or earlier, when leading the league in homers was more a matter of speed than power. Similarly, Trout would become only the second post-Mays player to have led his league in steals and total bases, following Jacoby Ellsbury, who took the AL total bases title in 2011. Trout is already only the eighth player ever to have led his league in steals and RBI; half of that group debuted in the 19th century, and no new players joined between Jackie Jensen in 1955 and Trout in 2014. (If strikeouts were one of our categories, we could keep going; Trout is the only player more recent than Frankie Crosetti—who debuted in 1932—to have led his league in both steals and strikeouts.)

In light of his career-long tendency to evolve from year to year, the odds are against Trout stopping at 10 categories. His 12 hit by pitches this season are a career high, and he trails Shin-Soo Choo by just two; if he doesn’t catch up this season, he might pick up the plunking pace in some future year. Trout finished second in the AL by eight plate appearances in 2013 and tied for sixth in games in 2015; if the Angels ever construct a 𝓀𝒾𝓁𝓁er lineup and put a playoff team around him, he’ll hit more often and possibly sit less often, giving him a greater chance of getting the games or PA marks.

The ultra-selective Trout of 2019 walks too often to lead the league in hits, but he’s still a staple of the top 10 in batting average. Trout lost the batting title to Cabrera by four points in 2012, but with a little luck, his refined sense of the strike zone and increasing contact rate could translate to another run at that trophy. However, his best days for doubles and triples are probably behind him. Trout’s nine triples in 2013 and 2014 trailed the league leaders’ totals by one, and his 39 doubles in those same seasons also placed toward the top of the league, but Angel Stadium suppresses non-homer extra-base hits, and his totals in both columns have declined.

On June 21, I observed that despite Trout’s excellence, the otherwise-lackluster Angels have been one of the .500-est teams of all time. That’s just as true today: Since the start of 2017, the Angels’ seasonal record has stood within five games of .500 392 times. If they finish within five of .500 nine more times in their remaining 47 games, they’ll break the three-year record of 399 set by the 1991-93 Cubs. (At 56-59, they’re guaranteed at least two more games within that narrow, mediocre range.) By contrast, Trout entered Tuesday projected to finish with 10.3 FanGraphs WAR, which would be a career high. He’s arguably never been better.

That’s nice to know. But it’s even more satisfying to savor how he got here. Prior to 2011, when Baseball America dubbed Trout the second-best prospect in baseball, the publication pronounced that he had “the potential to hit 20 or more homers annually.” Now he’s leading the league. His arm was once a weakness, and now it launches lasers. Trout walks way more than he used to, whiffs way less than he used to, and doesn’t steal as often. It may be mind-blowing that he’s averaged more than 9.0 WAR per season since his first full year, but the beauty is in the variable building blocks underneath that number.

WAR makes the most convincing argument for Trout as an unparalleled player, but his suite of league-leading older-school stats is special, too. Trout ranks 90th among all players in career WAR, according to Baseball-Reference. But if the season ended today, he’d be tied for 70th all-time in the Black-Ink Test, a 25-year-old Bill James–designed metric that appraises players based on how often they’ve led the league in the most basic stats. As impressive as WAR reveals him to be, we could recognize his greatness without park factors and positional adjustments, just by scrutinizing the stats that were on the backs of baseball cards long before WAR was welcome.

In an MLB promo released last month, Trout intoned, “Maybe I’m not what everyone wants me to be, but I’m exactly who I’ve always been.” Maybe that’s true off the field. In uniform, though, Trout at 28 is exactly what we want him to be: someone different from—and in some ways, improbably better than—the player he’s been before.