Growing Up

Ida B. Wells was not yet three when the Civil War ended and slavery was abolished, so she had no personal memory of being enslaved. But she heard her parents’ stories and saw the scars on her mother’s back from beatings she had suffered. Slavery was a stark reality for Ida, but her own 𝘤𝘩𝘪𝘭𝘥hood was spent in, and shaped by, Reconstruction. From 1865 to 1877, the federal government established the ground rules for Southern states’ readmission to the Union, and federal troops kept order in the South. Black Americans gained freedom, citizenship, and the right to vote during these years. They also contended with fear, poverty, and the sometimes violent hostility of many whites.

Ida grew up in Holly Springs, Mississippi, the oldest of eight 𝘤𝘩𝘪𝘭𝘥ren. Her parents, James and Elizabeth Wells, learned to read after slavery and made sure their 𝘤𝘩𝘪𝘭𝘥ren were educated. James had been trained as a carpenter and was able to support his family without becoming a sharecropper, the fate that kept so many Blacks in conditions similar to slavery. He was self-sufficient, determined, and proud. When his former owner’s wife asked him to visit, he refused. In 1867, when Black men in Mississippi could vote for the first time, his white employer told him to vote for the Democrats, but again he refused.

When Ida was 16, her family faced a terrible tragedy when her parents and 𝑏𝑎𝑏𝑦 brother died of yellow fever. The six remaining Wells 𝘤𝘩𝘪𝘭𝘥ren were orphaned, and Ida “suddenly found myself head of a family.” She went to work as a schoolteacher. She also continued her own studies, taught Sunday school, and did the family’s cooking, washing, and ironing. Three years later, in 1881, Ida and her two youngest sisters moved fifty miles away to Memphis, Tennessee, to live with their aunt, where Ida continued to teach.

Meeting Jim Crow

The South was changing. Reconstruction was over. A harsh new system called Jim Crow was gradually constricting Black people’s rights and freedoms and enforcing segregation, often through intimidation and violence. Jim Crow was eventually written into law, but much of it was based on social customs and the whims of individuals, as Ida learned.

When she was 22, Ida bought a first-class ticket on a train from Memphis to Holly Springs and took a seat in the ladies’ car, something she had done for the previous two years. This time, however, the conductor told her to move. Ida resisted, and when he tried to drag her from her seat, she bit his hand. Two men helped him forcibly remove her as white passengers applauded.After she was removed from the train, she sued the railroad for damages and won, but her triumph was short-lived, as the railroad won on appeal. Jim Crow was becoming the law of the land.

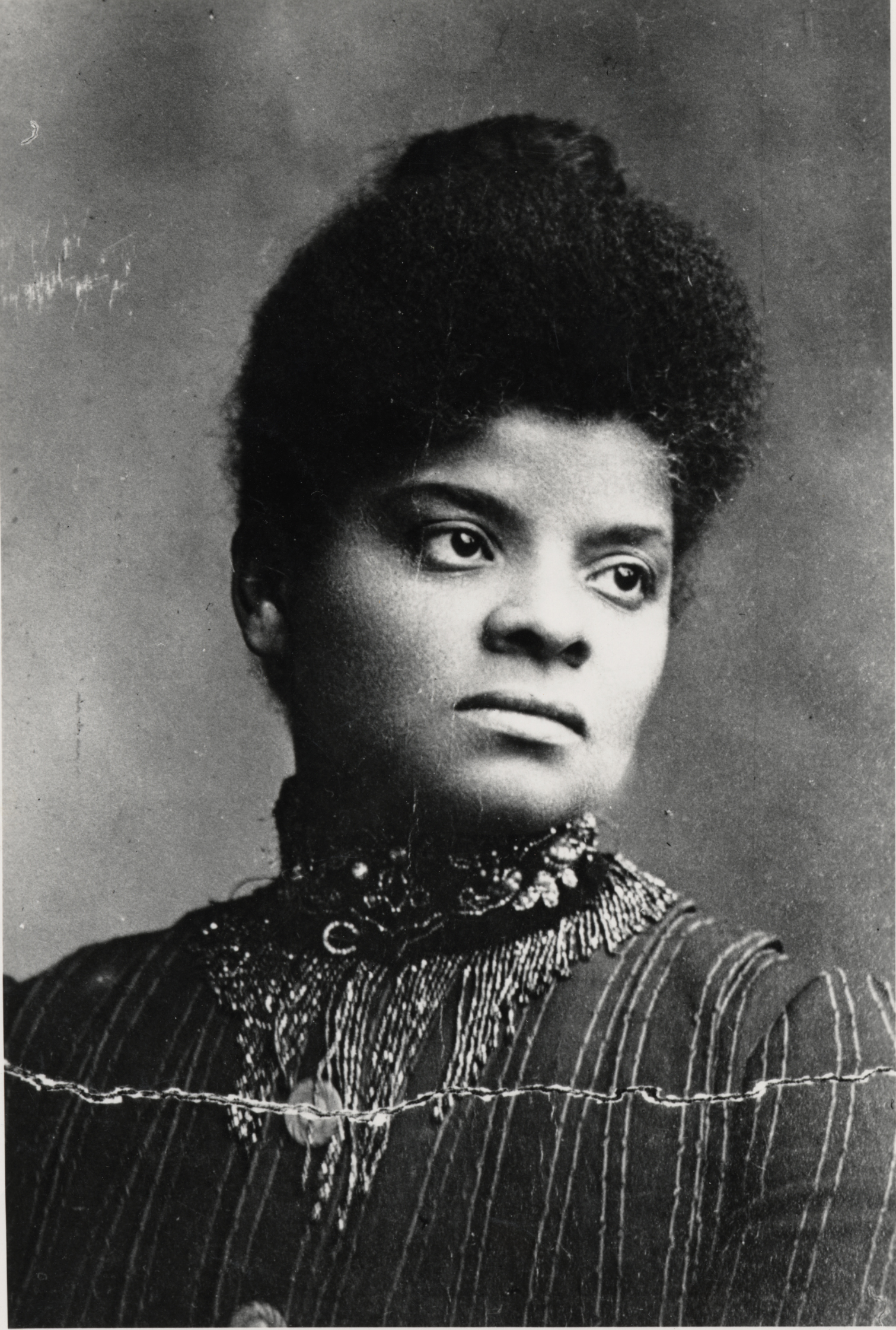

In 1886, when she was 24, Ida lost her teaching job after she criticized conditions in the Memphis schools. She had written a few articles for newspapers and decided to turn to journalism full time. Three years later, she bought a share in the Memphis Free Speech and Headlight and was appointed its editor. She was the first female co-owner and editor of a Black newspaper in the US. She began writing articles and editorials under the name “Iola.”

Crusader Against Lynching

The major turning point in Ida’s life came in 1892. Her friend Thomas Moss, a Memphis letter carrier and grocer, was lynched by a mob after confrontations with rival white grocers. Shocked, Ida bought a pistol and wrote an editorial urging African Americans to move out of Memphis for their safety. Then she began to focus her work on the rise in lynchings in America.

By the 1890s, lynching was a terrorist campaign to solidify white control of the South. Victims were often Black men accused of raping white women. Ida doubted these accusations, noting that often the charge was made after a man had been hanged or burned or shot or beaten. She thought it more likely that victims had been in a consensual relationship with a white woman or, like her friend Thomas Moss, were businessmen who threatened rival whites and had no connection to white women at all.

Ida wrote a series of anti-lynching editorials. The last one suggested that white women could find Black men romantically appealing, and she headed north for three weeks as it hit the newsstands. Editors of white newspapers in the South reprinted the editorial and called for white men to avenge their women. While she was in New York, Ida learned of threats against her and against her friends and family. The offices of her newspaper were burned. It was clear she could not return to Memphis. From then on she lived in the North, mostly in Chicago, and changed her pen name to “Exiled.”

Ida documented 728 lynching cases that had occurred between 1884 and 1892, using research by the Chicago Tribune. Within months of her friend’s murder, she wrote a collection of articles under the title Southern Horrors. She focused less on grisly details and more on the false accusations made against the victims. Her goal was “to arouse the conscience of America,” and she became America’s best-known crusader against lynching.

Suffragist

Ida was also a staunch supporter of women securing the right to vote. She published “How Enfranchisement Stops Lynching” in Original Rights Magazine in 1910, showing that when Black voters in Illinois elected a Black state legislator in 1904, he worked to pass a law against mob violence. She co-founded the Alpha Suffrage Club in Chicago in 1913, which became the largest Black women’s suffrage organization in Illinois. In addition to supporting women’s efforts to obtain the vote, the Alpha Suffrage Club taught women how to be politically active and promoted Black candidates for office.

Ida marched in the 1913 suffrage parade in Washington, DC, when many of the organizers resisted Black women’s participation in the parade. After Black women were told they would march in segregated sections, the NAACP organized letter and telegram protests. The parade organizers relented and Black suffragists, including Ida, marched in their state and occupational delegations.

Later years

She continued her work for decades, traveling abroad to decry lynching and raise money and working with women’s clubs to encourage political participation, even running for state office herself. In 1922, she supported an antilynching bill then before Congress. Because of Democratic opposition, the bill failed, as did all federal efforts to end lynching, white supremacy’s weapon of terror.

In 2018, the National Memorial for Peace and Justice opened in Montgomery, Alabama, to commemorate more than 4,400 African American men, women, and 𝘤𝘩𝘪𝘭𝘥ren lynched between 1877 and 1950. In 2020, Ida was awarded a posthumous Pulitzer Prize in recognition of her “outstanding and courageous” reporting about lynching.