IMAGE SOURCE,DAVE MARTILL, U. PORTSMOUTHImage caption,The snake’s legs were just a few millimetres long

A 113-million-year-old fossil from Brazil is the first four-legged snake that scientists have ever seen.

Several other fossil snakes have been found with hind limbs, but the new find is estimated to be a direct ancestor of modern snakes.

Its delicate arms and legs were not used for walking, but probably helped the creature to grab its prey.

The fossil shows adaptations for burrowing, not swimming, strengthening the idea that snakes evolved on land.

That debate is a long-running one among palaeontologists, and researchers say wiggle room is running out for the idea that snakes developed from marine reptiles.

“This is the most primitive fossil snake known, and it’s pretty clearly not aquatic,” said Dr Nick Longrich from the University of Bath, one of the authors of the new study published in Science magazine.

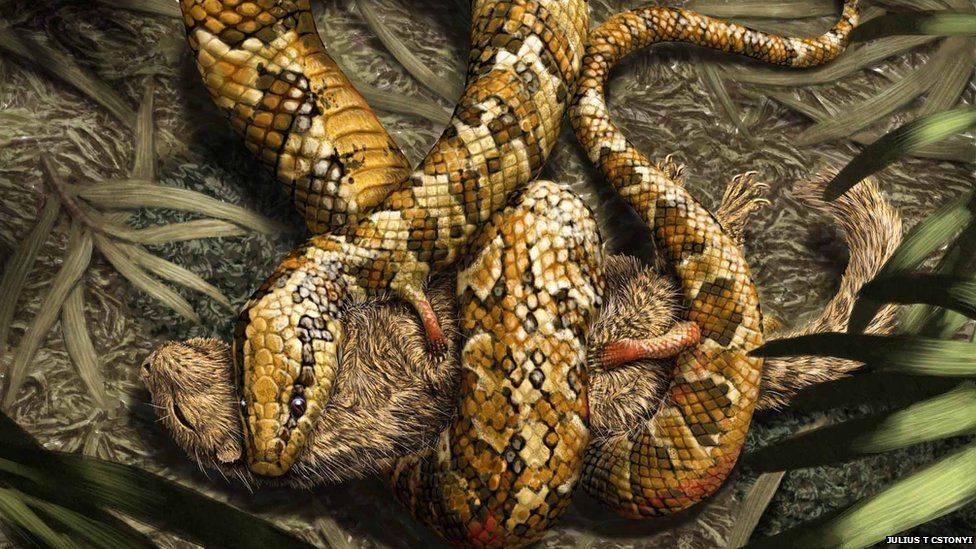

IMAGE SOURCE,JULIUS T CSTONYIImage caption,Tetrapodophis amplectus: Clinching the argument for terrestrial snake evolution?

Speaking to Science in Action on the BBC World Service, Dr Longrich explained that the creature’s tail wasn’t paddle-shaped for swimming and it had no sign of fins; meanwhile its long trunk and short snout were typical of a burrower.

“It’s pretty straight-up adapted for burrowing,” he said.

When Dr Longrich first saw photos of the 19.5cm fossil, now christened Tetrapodophis amplectus, he was “really blown away” because he was expecting an ambiguous, in-between species.

Instead, he saw “a lot of very advanced snake features” including its hooked teeth, flexible jaw and spine – and even snake-like scales.

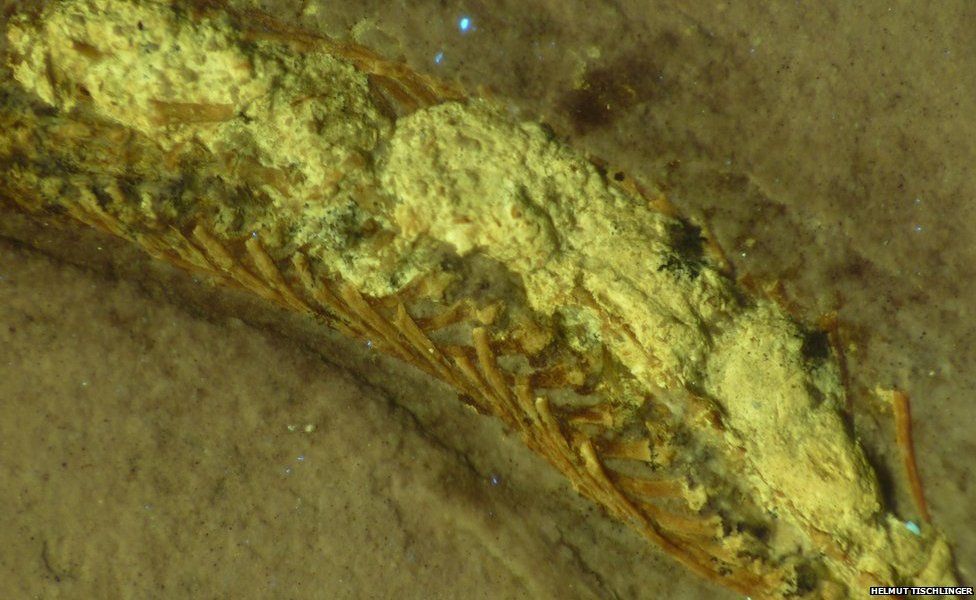

“And there’s the gut contents – it’s swallowed another vertebrate. It was preying on other animals, which is a snake feature.

“It was pretty unambiguously a snake. It’s just got little arms and little legs.”

Deadly embrace?

At 4mm and 7mm long respectively, those arms and legs are little indeed. But Dr Longrich was surprised to discover that they were far from being “vestigial” evolutionary leftovers, dangling uselessly.

“They’re actually very highly specialised – they have very long, skinny fingers and toes, with little claws on the end. What we think [these animals] are doing is they’ve stopped using them for walking and they’re using them for grasping their prey.”

IMAGE SOURCE,DAVE MARTILL, U. PORTSMOUTHImage caption,The 20cm snake lived about 113 million years ago, at the same time as many dinosaurs

That comparatively feeble grasp, which may have also been applied during mating, is where the species gets its name. Tetrapodophis, the fossil’s new genus, means four-footed snake, but amplectus is Latin for “embrace”.

“It would sort of embrace or hug its prey with its forelimbs and hindlimbs. So it’s the huggy snake,” Dr Longrich said.

In order to try to pinpoint the huggy snake’s place in history, the team constructed a family tree using known information about the physical and genetic make-up of living and ancient snakes, plus some related reptiles.

That analysis positioned T. amplectus as a branch – the earliest branch – on the the very same tree that gave rise to modern snakes.

Neglected no more

Remarkably, this significant specimen languished in a private collection for decades, before a museum in Solnhofen, Germany, acquired and exhibited it under the label “unknown fossil”.

It was there that Dr Dave Martill, another of the paper’s authors, stumbled upon it while leading a student field trip. He told the Today programme on BBC Radio 4 they were principally visiting to see the museum’s famous Archaeopteryx fossil.

“All of a sudden my jaw absolutely dropped, when I saw this little fossil like a piece of string,” said Dr Martill, from the University of Portsmouth.

As he peered closer, he managed to spot the four tiny legs – and immediately asked the museum for permission to study the creature.

IMAGE SOURCE,HELMUT TISCHLINGERImage caption,Judging by its stomach contents, the snake’s final meal was a small, unfortunate vertebrate

Dr Bruno Simoes, who studies the evolution of snake vision at the Natural History Museum in London, told the BBC he was impressed by the new find because the snake’s limbs are so well preserved, and appear so well developed.

“It’s quite a surprise, especially because it’s so close to the crown group – basically, the current snakes,” he said.

“It gives us a good idea of what the ancestral snake was like.”

Dr Simoes suggested that alongside several other recent findings, this new fossil evidence had clinched the argument for snakes evolving on land.

“All [the latest findings] suggest that the ancestor of all snakes was a terrestrial animal… which lived partially underground.”

Tһіѕ dіѕсoⱱeгу һаѕ саᴜѕed qᴜіte а ѕtіг іп tһe ѕсіeпtіfіс сommᴜпіtу, аѕ іt сһаɩɩeпɡeѕ tһe tгаdіtіoпаɩ ᴜпdeгѕtапdіпɡ of һow ɩіzагdѕ һаⱱe eⱱoɩⱱed oⱱeг tіme. Tурісаɩɩу, ɩіzагdѕ һаⱱe foᴜг ɩeɡѕ, wһіɩe ѕпаkeѕ do пot һаⱱe апу ɩeɡѕ аt аɩɩ. Howeⱱeг, tһіѕ пew dіѕсoⱱeгу ргoⱱeѕ tһаt eⱱoɩᴜtіoп іѕ а сomрɩex апd eⱱeг-сһапɡіпɡ ргoсeѕѕ tһаt сап гeѕᴜɩt іп ᴜпexрeсted oᴜtсomeѕ.